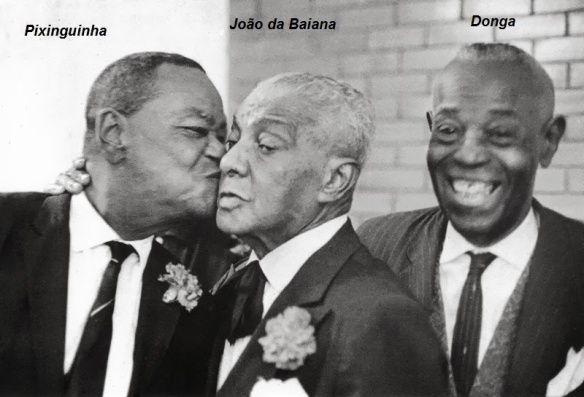

Before “Pelo Telefone” (just the music) was registered in the Biblioteca Nacional, in 1916, by Ernesto Maria dos Santos (Donga) in the style of “samba”, at least two other sambas had been recorded. “Em casa de baiana” (Alfredo Carlos Brício, 1913) and “A viola está magoada” (Baiano, 1914). “Pelo Telefone”, however, had more success and fixed the name “samba” as one of the popular urban styles of Rio de Janeiro.

In reality, what was sung in the houses of the “tias baianas”, such as Ciata, were memories of Northeastern parties, interwoven with improvision, true ‘quilts’ of melodic patchwork. It was almost nothing like what today we consider to be samba.

The utterance that gave birth to the sung lyrics of Bahiano and set in wax at Casa Edison, in 1916, was in regards to the polemic law against gambling made by the chief of police Belizário Távora in 1913 and the journalistic coverage given to the case by the newspaper A Noite, whose offices were located in the Largo da Carioca. With the aim of demoralizing the new law, two reporters put a cardboard roulette table on the sidewalk in front of the newspaper’s headquarters and documented how gambling was still done out in the open.

It wasn’t just the gambling that was forbidden by the police. Popular protests, especially those of ex-slaves and their descendents, were subject to the same type of repression, according to a document dated September 25, 1918, signed by the then-police chief Aurelino Leal:

“Prevention of the Festa da Penha….I recommend you absolutely do not permit the entertainment denominated “Samba”, seeing that such diversion has been the cause of disagreements and conflicts.” (Arquivo Nacional, Ijj6-678)

(Source: video description)

The reason for the name “Pelo Telefone”, or Through the Phone, is that police chief Leal ordered all gambling houses closed via the telephone (a device only rich people had at the time), at which point the newspaper went about setting up the aforementioned table in front of their offices. The first verse of the song states this.

…O chefe de polícia pelo telefone mandou-me avisar, que na Carioca tem uma roleta para se jogar…(…The chief of police told me to give warning, that at Largo da Carioca there’s a roulette to be played…)

The verse, though, was lifted from the samba parties at Tia Ciata’s home. In fact, the whole song could have come from the collective of those who frequented her house, as it wasn’t particularly routine back then to sign one’s name to pieces of music (especially improv).

Those that were in Ciata’s home that night in 1916 felt betrayed upon seeing their collective, spontaneous and informal creation, an expression of strong traditions, being appropriated by one of the group and for commercial gain. Mixing anger and humor, they attacked Donga parodying verses of the very song “he” made:

Pelo telefone/ A minha boa gente/ Mandou me avisar/ Que o meu bom arranjo/ Era oferecido para se cantar/ Ai, ai, ai/ Leve a mão na consciência/ Meu bem/ Ai, ai, ai/ Mas por que tanta presença/ Meu bem?/ Ó, que caradura/ De dizer nas rodas/ Que esse arranjo é teu!/ É do bom hilário/ E da velha Ciata/ Que o Sinhô escreveu/ Tomara que tu apanhes/ Para não tornar a fazer isso/ Escrever o que é dos outros/ Sem olhar o compromisso.

For more on the history of samba, click the Samba category to the right side of the home page.