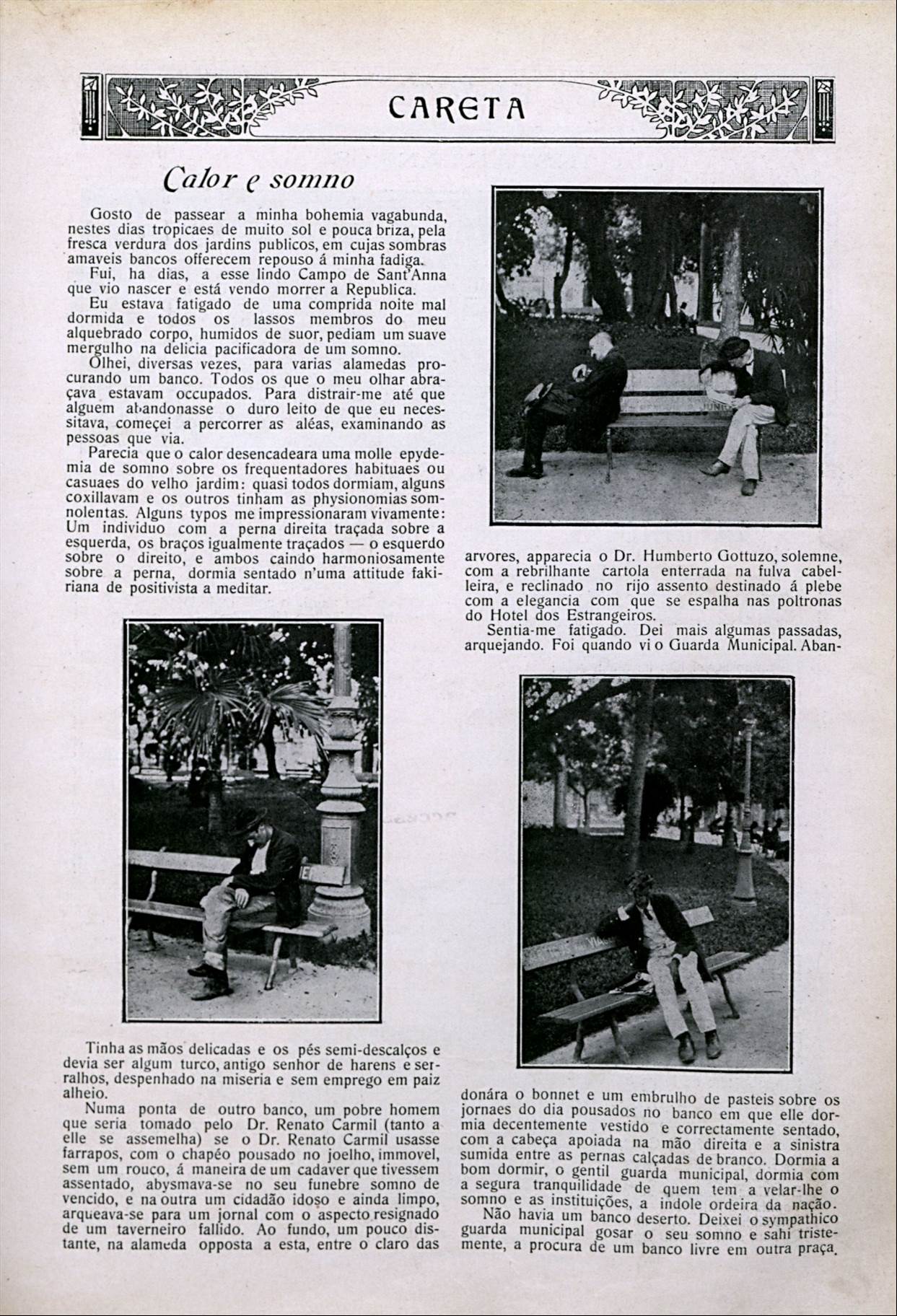

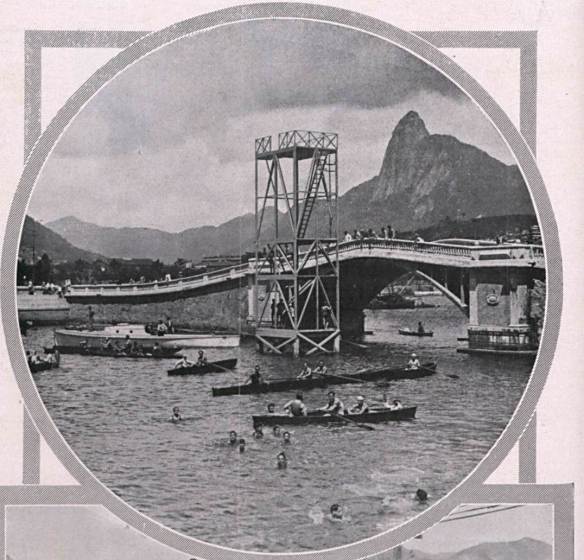

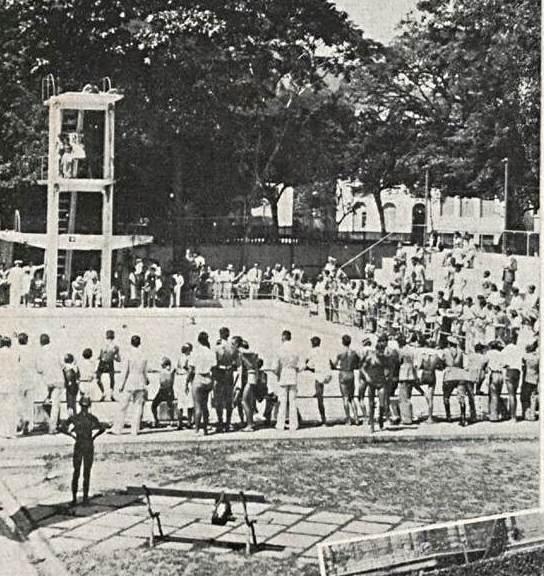

Inauguration of Tijuca Tennis Club pool (Revista da Semana, 1931)

I really enjoy tracking down small but interesting aspects of Rio’s past, such as with the Carnival song, the Arpoador house, or the Flamengo wall, I came across yet another “lost memory”, as it were, and have tried for the last week to track down a photo and more information but it was proving very difficult, despite using all my resources. The lost memory in question, regarding public pools on the beaches (a curious thing to imagine), is below:

In the 1930s, Ipanema finally got an urbanistic project that proposed the leveling of the sand and the greening of the area closest to the street, with the planting of coconut tree seedlings. At this time, two public pools were also built. One on Arpoador and the other at the start of Avenida Niemeyer, in Leblon, and as they never were successful they ended up being demolished. (source, PT)

I did find another short reference to the same thing, but it doesn’t differ much from the source above:

Arpoador, on the other hand, had a public pool at the end of 1937, which was inaugurated by Mayor Dodsworth (who inaugurated another in Leblon, at the start of Avenida Niemeyer), which existed for little time. (source, PT)

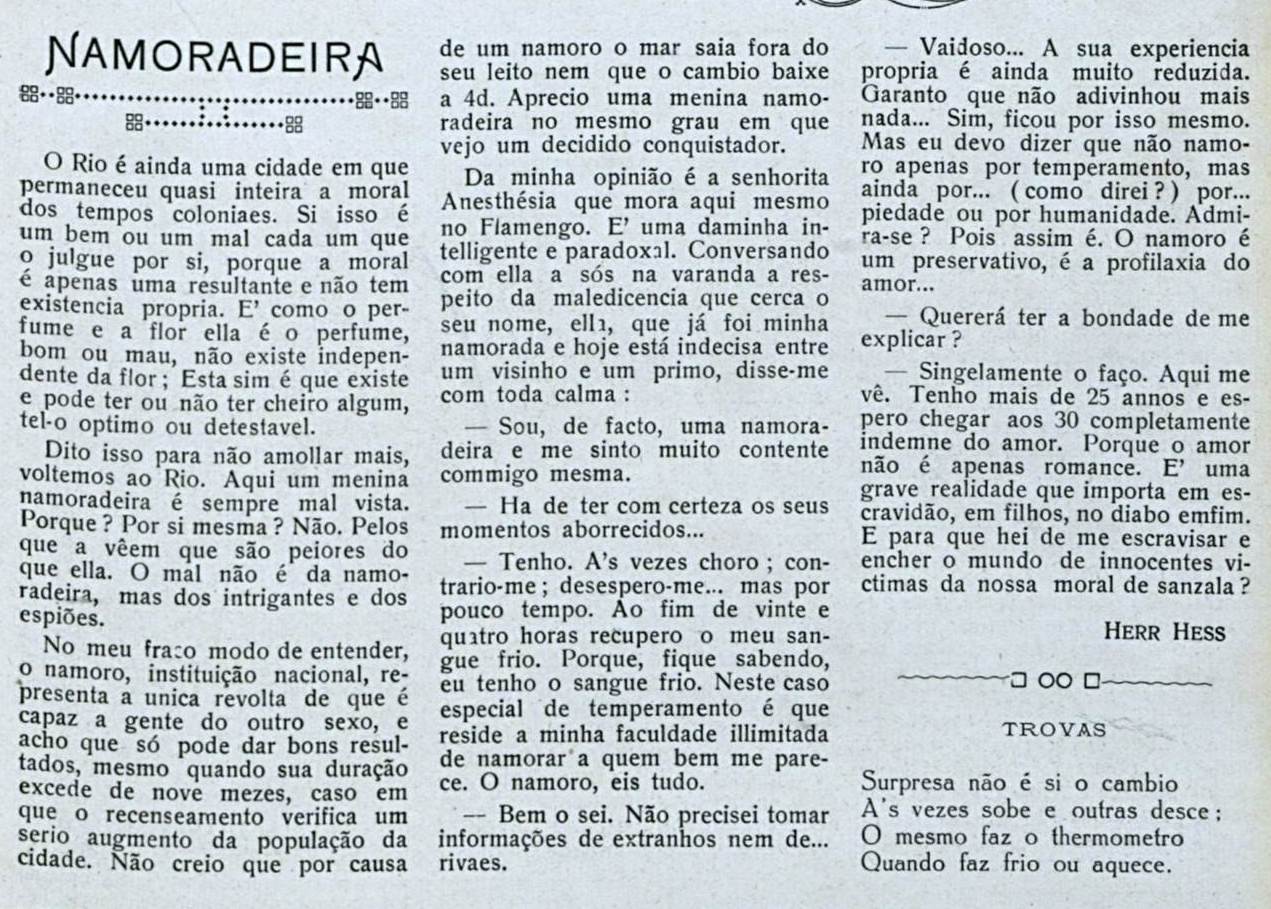

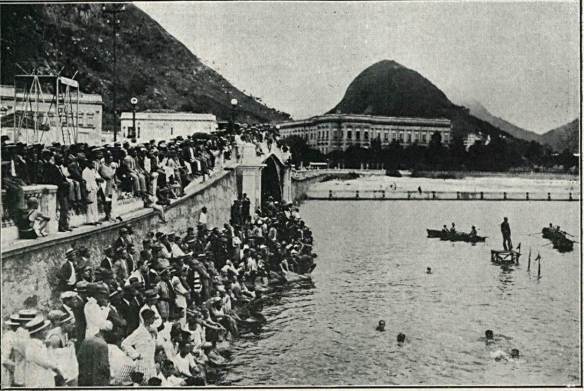

C. R. Guanabara pool (Careta, 1936)

C. R. Guanabara pool (Careta, 1935)

As for why Mayor Henrique Dodsworth might have built public pools, it seems he used his term in office to transform the city in several ways:

His government was marked by major construction and redevelopment of regions in the center of the city. The opening of Avenida Presidente Vargas […], the beginning of construction on Maracanã and the Grajaú-Jacarepaguá Highway were also started by the politician. (source, PT)

More specifically, the number of public pools in the city at the time was quite limited:

The Federal District has four pools: Guanabara; Fluminense; Tijuca and Clube de Regatas Botafogo, excluding the private ones. There are others in the project phase, and with the possibilities of being built: C.R. Flamengo, C.R. Vasco da Gama, and Botafogo F.C.

( Correio da Manhã, pg 9, 05-23-1937)

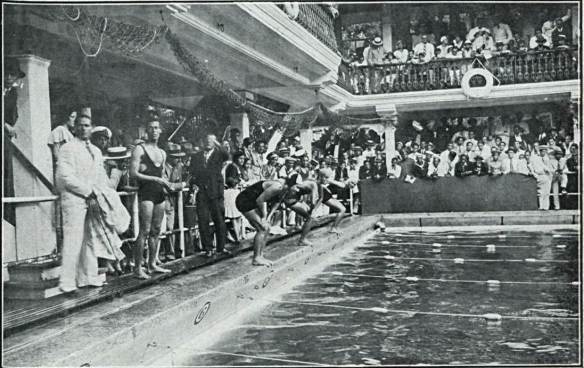

Urca pool (Careta, 1922)

Urca pool (Careta, 1930)

In an article from around 10 years earlier, an author critisizes the city’s lack of pools and provides reasons why:

Public Swimming Pools

It seems absurd at the first moment to hear that in Rio, its inhabitants have almost no places where they can safely and comfortably practice the so healthy and beautiful sport of swimming, but this is true. We are really surrounded by the sea, but with the criterion adopted of destroying the beaches for the construction of the seafront avenues, our capital currently has relatively few beaches in its most populous and busiest part.

In addition, not on all beaches the inhabitants of the city can count on the means of security; for the practice of swimming, nor with the necessary comfort, such as changing rooms and cabins for changing clothes, and for that reason, our beaches are almost only accessible to people living in their vicinity.

The swimming pools built in various areas of the city would greatly benefit its population, especially the large part of them, who cannot enjoy the baths in Copacabana and who have to resort in summer to the small and dirty beaches of the city.

In the United States and other countries, even in cities that have beaches, their City Halls set up public swimming pools, for whose use the public is charged a small amount. The main purpose of the swimming pools is to increase the taste for swimming, undoubtedly one of the best and most beautiful sports, and to free those who wish to practice it from the treacherous dangers of the sea.

Our City Hall could use the sea water, where possible, and build some swimming pools in certain areas of the city, charging the public for their use a small amount, which would serve to cover the expenses with the conservation and care of those. Ponta do Calabouço, for example. close to the site where the majestic headquarters of four veteran nautical centers of the city will emerge, it would be an excellent place for a public swimming pool which would render a lot of service to the population of the city that lives in its central part. The sea there, today without a beach, is treacherous and has often sacrificed the lives of those who, recklessly, risk swimming there.

In the Urca district there is already a swimming pool, which is now sadly abandoned. Why doesn’t our City Hall begin what we asked for with the reconstruction and cleaning of this swimming pool that was once so frequented by swimmers in Botafogo and where the Rowing Federation had its official [new?] contests?

(Jornal do Brasil, pg 5, 08-06-1926)

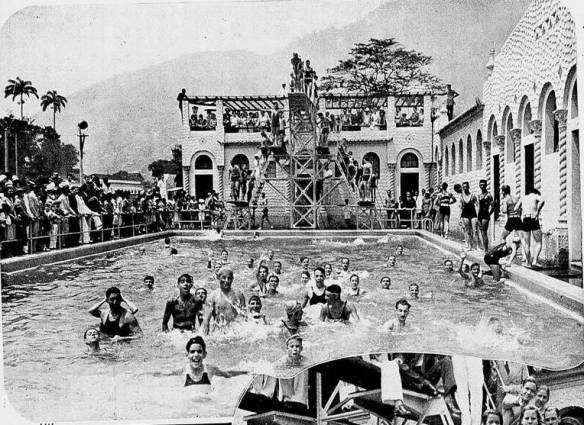

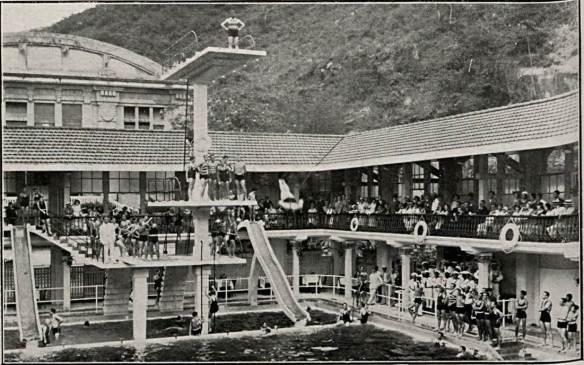

Fluminense Football Club pool (Careta, 1932)

Fluminense Football Club pool (Careta, 1931)

Newspaper archives reference several public pool initiatives from the years between 1937 and 1939, during Dodsworth’s term, including a request by an Olympic swimmer:

Piedade Coutinho asked the mayor to collaborate in the construction of a public swimming pool. Mr. Henrique Dodsworth promised to enter […] Guanabara Bay and Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, as a bonus.

(O Imparcial, pg 2, 12-18-1937)

Curiously, in an article from two years later, it’s mentioned that Dodsworth is planning a series of public pools in Rio, starting in the suburbs and culminating with pools near the beaches, which would mean that the second reference above, of public pools in Arpoador and Leblon in 1937, is probably inaccurate. I reached out to the author of the book in question from which that information was sourced and she graciously pointed me towards the location where I can find more details, given that I find myself in Rio again. Regardless, these projects take time to plan and build, so I don’t see how the public pools project from 1939 mentioned below could have reached the beaches in the same year, as the first reference at the top states.

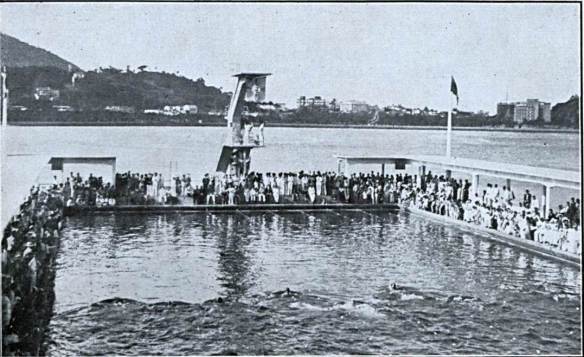

C. R. Botafogo (Careta, 1937)

Popular Swimming Pools

It appeared in the newspapers that Mr. Mayor has just opened up credit for the construction of a public swimming pool in one of our farthest suburbs.

The initiative is the most commendable, and we are certain that the pool now decided for Realengo will be the first of a series of swimming pools with which the City Hall will progressively equip all neighborhoods.

Until now, the lack of water in abundance was enough to justify that the District administration did not decide on the construction of these public bathing spots.

If sometimes there was no water for drinking, it was not possible to admit that it was enough for hygiene and sports at the same time. But water is coming, according to the most truthful information, in sufficient quantity for all its useful uses. Therefore, it is time to start providing the people with that comfort, which our climate sorely demands.

The series of swimming pools logically started where it should start. In fact, the first ones should be installed in the suburbs farthest from our beaches.

Afterwards, they will multiply towards the coast, in whose neighborhoods they constitute a precious complement to our sports equipment and to the hygiene rooms of those who visit our beaches.

Hoping that Realengo’s swimming pool will be the starting point of a program to provide public swimming pools to all neighborhoods, we would like to express our applause to this initiative, so logically demanded by our tropical environment.

(Jornal do Brasil, pg 5, 12-27-39)

Despite all this talk about how many pools Rio had at the time or how many they would build – after searching newspapers and magazines from 1920 to 1950 – I could find zero pictures of said, supposedly-built, pools but regarding the existing pools of the time I did find the photos included in this post (and many more). Despite not being able to locate any real evidence of the public pools project that Dodsworth apparently spearheaded, I’m hoping that I was able to build a picture, as it were, of the situation at the time.